At Waterside School in Stamford, CT, students are not only getting a top-notch education, but support and community to last well beyond their elementary school years.

Christina Roca knew her parent-teacher conferences were different from those of other students at Greenwich Country Day. Roca was born in the U.S.; her parents are immigrants from Guatemala and Honduras, and she recalls, “I would sit in those meetings to translate for them.” That made extra work for her, but Waterside gave her extra support. “I knew I wasn’t the only one going through that from my class at Waterside,” she says, referring to the elementary school she attended before going to middle school at Greenwich Country Day. “I knew I could always go back to Waterside and ask for support.”

She did just that, returning even more frequently as she prepared to graduate high school at Miss Porter’s School. “My Waterside teachers and advisors were formative as I started the college process, especially as a first-generation college student,” Roca recalls. “They had boot camps about how to apply to colleges and compare aid packages, ACT and SAT prep over the summer. People think ‘oh, Waterside is an elementary school,’ but it’s not just that; it opens doors and establishes bridges.”

Opening doors that might otherwise be locked shut is the mission of Waterside School, which was established in 2001 as an independent school accepting children only from underserved communities, and preparing them to go on to leading middle schools, high schools, colleges and universities. The end goal, the website says, is for alums to “become the leaders of tomorrow.”

Duncan Edwards, who became executive director of Waterside in 2003 after 14 years as head of the Brunswick School and a brief stint as CEO of the international relief organization Americares, joined the school thinking, “the mission couldn’t be any more noble or the financial model any worse,” he says, “An independent school striving to be of the absolute highest quality with every child on scholarship and tuition revenue covering the smallest fraction of operating expenses? I was not sure it was doable. But the mission was so noble that I had to try.”

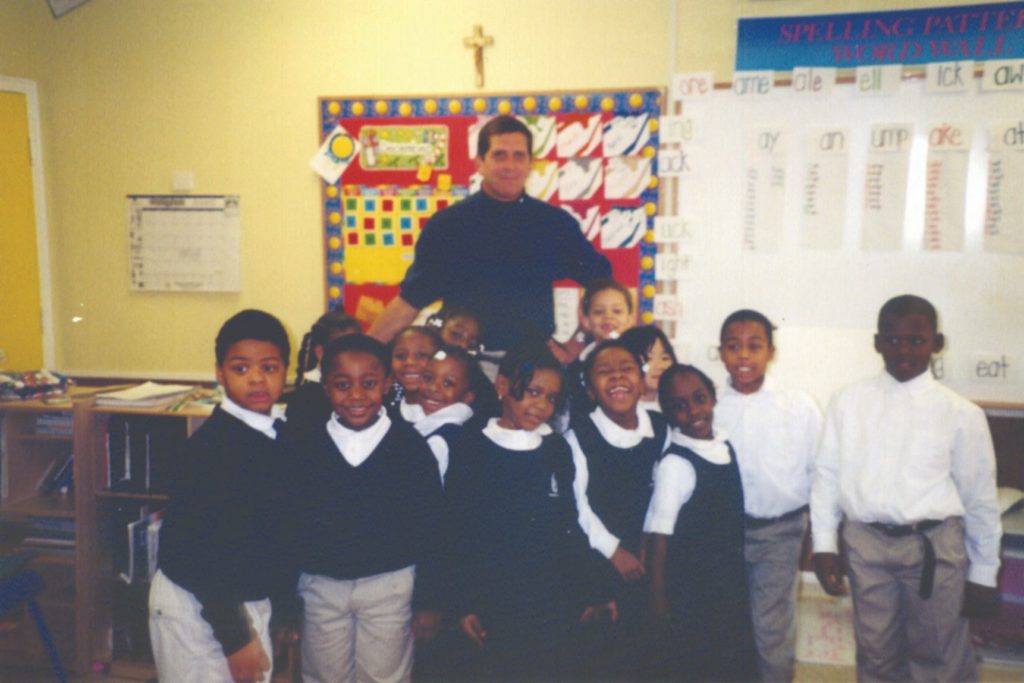

It took a lot of trying to turn the Waterside of 2003—which had a grand total of 27 students learning in rented office space behind a church—into today’s multistory stone temple to learning in downtown Stamford, CT. First, in 2004, Edwards brought Jody Visage to the school from Greenwich Academy. At that time, says Visage, “Waterside was just four rooms and people with a huge amount of spirit holding it together with Scotch tape—but there was such a strong underlying desire to make this happen for our kids.”

Then, in 2006, Waterside graduated its first class of fifth graders. “We sent children off to Brunswick and Greenwich Country Day and Greenwich Academy, to the finest schools in the area,” recalls Edwards. “And people understood that as a measure of success.”

Although Waterside almost closed several times due to lack of funds, Visage recalls, “Every time it looked like we wouldn’t be able to continue, some new source of support would come and we’d be able to move forward.” In April 2010, Waterside broke ground on its own campus, still $9.5 million short of the required capital raise. But 14 months later, the new Waterside opened its doors, as Edwards says, “without a dollar of debt.” Today, the school is at full capacity with 145 students, and alums regularly graduate from top schools.

The secrets to Waterside’s unexpected success aren’t secret. Both Edwards and Visage cite the small class size, which enables them to teach children in differentiated groups at exactly the level, and with the specific kind of materials and techniques, that they need.

Even more important is the commitment of the parents, who pay tuition to the best of their ability, volunteer at the school, and attend mandatory parent-teacher conferences, which are required by a contract each family signs—a document drawn up by the parents themselves. As Edwards says, “We demand an awful lot of our parent body, and they answer every call.” Like the students, Waterside’s parents also consider Waterside a resource they can return to; “I remember my mom going back all the time seeking help for filling out FAFSA or tax forms,” says Roca.

“Waterside is very much like a family,” Visage explains, citing the way students continue to receive love and support long after graduation. Megan Evans, who started at Waterside as a co-teacher, now works as director of placement, helping students apply to leading independent schools and, in time, colleges and universities. The school’s alumni program works to provide summer internships and jobs post-graduation. Evans sees her job as not only helping students find the perfect place for themselves, but also empowering them to believe they can succeed.

“I had an alum who came to me and said, ‘My high school counselor really doesn’t think I can get into Middlebury. It’s my dream school, but they’re saying I should apply to X, Y, and Z.’” Evans remembers.

“That’s where I’m like, ‘Nope! You’ve been working your butt off since you were in kindergarten at Waterside. You are applying to Middlebury Early Decision, and if you don’t get in, then you apply to these other schools.’” He was accepted. “In those moments,” says Evans, “I just feel honored to be a small part of their journey.”

Many Waterside alumni enter the world affecting change in not only their own lives, but their communities. “What keeps me motivated is seeing the kids go on to be true changemakers in their next schools,” says Evans. “I recently saw a video of one of my former students giving the annual speech at her school, talking about being a Black woman at a predominately white institution and how that has shaped who she is. The crowd was cheering and crying. I think of her as a fourth grader running around at recess, and here she is sharing her experience in a way that’s going to be truly transformative for that institution.”

Lisa Stuart, chair of the board at Waterside, says area businesses have been impacted by the school as well. “We have something like 15 alums, mostly college sophomores, that Waterside has helped secure summer internships,” she says. “Recently, one of the board members said to me, ‘Look, I’ve got to be honest with you. My employees are getting more out of this than the student.’”

“WHAT KEEPS ME MOTIVATED IS SEEING THE KIDS GO ON TO BE TRUE CHANGEMAKERS IN THEIR NEXT SCHOOLS”

MEGAN EVANS

Now Waterside is about to embark on a new phase. Visage retired last year, but became a member of the board. Now, Edwards is moving on, leaving Waterside with a strong endowment, its own campus, “lots of great young talent in the building,” and under the leadership of David Olson, who was most recently the head of middle school at Sacred Heart in Greenwich, CT. “The school is strong and secure,” says Edwards. “But it will be impossible to walk away completely.”

That has proved especially true for Roca, who will be one of Waterside’s newest teachers next year. “Waterside gave me so much mentorship and support,” she says, “I would love to be the person who can provide that for future students.”